The Greater the Emptiness the Grander the Art

by Stefan Gronert

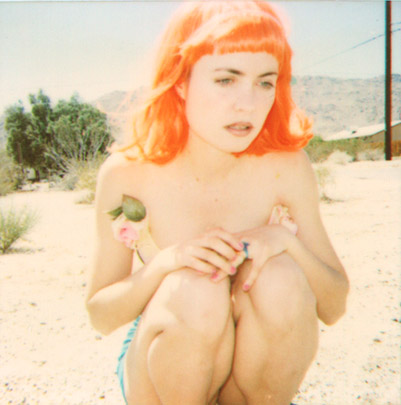

Not “Twenty-six Gasoline Stations” but “Twentynine Palms, CA”! Forty-two years after Ed Ruscha’s legendary book, there is no gasoline station at the beginning of the book that is here at hand. Instead it is the open-hearted Radha – with orange hair, pink-colored overalls and a bashful, or rather cunning, gaze that is directed downward – with which this book begins! And with her and with Max – attention: a woman –, one whose appearance is in accordance with the same styling, it comes to an end as well – after Radha has in the meantime colored her fingernails pink, again endowed with the same openheartedness and the same look which now, however, reveals in combination with her altered facial expression an “old-maidish” turning away from the viewer. This may serve as an example for a vivid and understandable transformation which flows into a large-scale representation of a cheerless settlement beneath a shining, blue sky – there a figure, lost straightaway, becomes overwhelmed.

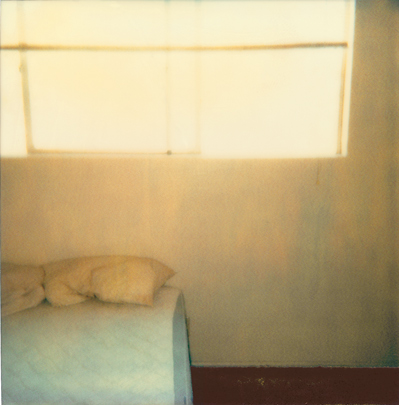

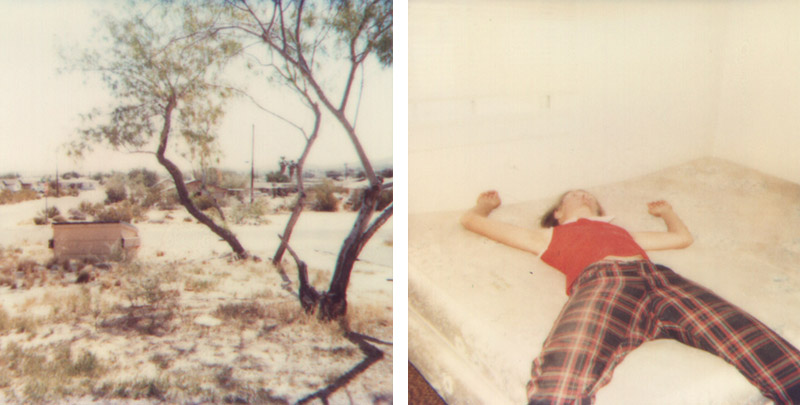

Pictures which in 1998/99 play in the harsh California sunlight or in spaces that are not exactly cozy and comfortable. “Play” is the correct word in this regard, for precisely in view of the pictures of persons, there remains more than just doubt as to whether we are looking at staged scenes or have simply happened upon the high-strung “reality” of a (wannabe) film world. Yet not all the pictures have the same character of a glaring, plastic world. Upon flipping through the pages, we also encounter unpretentious, literally “colorless” scenes in undefined interiors, or unspectacular views resembling a still life and opening out onto a nowhere land. That which connects all participants in these pictureworlds is the observation that they appear to be exhausted, lost, empty or uncertain about their existence. One is almost reminded of the empty gazes and loneliness of the protagonists in the pictures of large cities painted by Manet or Degas in the era of Early Modernism.

With one exception, all the photographs which are reproduced here, which originally measured 60 by 70cm but which here, in their present size and configuration, make productive use of the possibilities presented by the medium of the book, manifest several elements of B-movies: smoking, naked, made-up and muscular persons who are not inclined to conform entirely to the vision of Hollywood dreams. Beauty and vexation, eroticism and loneliness enter into a mixture which reveals the rift between desire and truth. From a distance, one is reminded of the “Untitled Film Stills” of Cindy Sherman, which in this regard are not nearly as drastic. Yet whereas her photos from the seventies are characterized by a cool, objective mode of representation in historicizing black-and- white, the photographs of Stefanie Schneider evince a soft, sometimes seemingly pictorial visual language with a coloration ranging from the pale to the artificial-glaring.

As in many other pictures of Stefanie Schneider which often present themselves to us as sequences, these photos refer back as well to the perceptual stereotypes of film. Making use of instant photography, proceeding from which significantly enlarged C-prints come into being, her pictures summon up the impression of a narration without ultimately becoming part of a plot that is readable in a linear fashion. The illusion of the narrative element, however, simply enhances the experience of a renunciation of just this aspect. For the picture titles as well – and also the title of this publication – provide no real help with the imaginary construction of a story. Nevertheless, names return which include the first name of the artist herself: hence is everything not in fact a game but rather a series of authentic and instantaneous images, or is it after all nothing other than a staging, a game – how real is life?

The paucity of plot elements, which contradicts all expectation of a cinematic style, as well as the emptiness and loneliness of the persons, enters into a peculiar, sometimes seemingly surreal association with the magic of the sun-drenched expanses of the dreamlike landscape. Just as the fantasy and imagination of the viewer are stimulated, so to the same great extent does the redemption of these visual figures of love founder on a void whose glaze is created, not least of all, by the peculiar blurriness of the photographic representation. The seemingly amateur character of these pictures, which have in no way been treated with any excessive scrupulousness, leaves us with a stimulating incertitude as to their interpretation, one in which the spheres of reality, fiction or dream are scarcely capable any longer of being differentiated. Thus the gaps and the scenic openness of what is presented ultimately set in motion a self-appraisal.

So what remains after “29 Palms, CA”? Perhaps that hope which deviates from the saying of Ruscha that is quoted in the title: “The stronger the photography the better the reality will be!”

translated by George Frederick Takis

Pictures which in 1998/99 play in the harsh California sunlight or in spaces that are not exactly cozy and comfortable. “Play” is the correct word in this regard, for precisely in view of the pictures of persons, there remains more than just doubt as to whether we are looking at staged scenes or have simply happened upon the high-strung “reality” of a (wannabe) film world. Yet not all the pictures have the same character of a glaring, plastic world. Upon flipping through the pages, we also encounter unpretentious, literally “colorless” scenes in undefined interiors, or unspectacular views resembling a still life and opening out onto a nowhere land. That which connects all participants in these pictureworlds is the observation that they appear to be exhausted, lost, empty or uncertain about their existence. One is almost reminded of the empty gazes and loneliness of the protagonists in the pictures of large cities painted by Manet or Degas in the era of Early Modernism.

With one exception, all the photographs which are reproduced here, which originally measured 60 by 70cm but which here, in their present size and configuration, make productive use of the possibilities presented by the medium of the book, manifest several elements of B-movies: smoking, naked, made-up and muscular persons who are not inclined to conform entirely to the vision of Hollywood dreams. Beauty and vexation, eroticism and loneliness enter into a mixture which reveals the rift between desire and truth. From a distance, one is reminded of the “Untitled Film Stills” of Cindy Sherman, which in this regard are not nearly as drastic. Yet whereas her photos from the seventies are characterized by a cool, objective mode of representation in historicizing black-and- white, the photographs of Stefanie Schneider evince a soft, sometimes seemingly pictorial visual language with a coloration ranging from the pale to the artificial-glaring.

As in many other pictures of Stefanie Schneider which often present themselves to us as sequences, these photos refer back as well to the perceptual stereotypes of film. Making use of instant photography, proceeding from which significantly enlarged C-prints come into being, her pictures summon up the impression of a narration without ultimately becoming part of a plot that is readable in a linear fashion. The illusion of the narrative element, however, simply enhances the experience of a renunciation of just this aspect. For the picture titles as well – and also the title of this publication – provide no real help with the imaginary construction of a story. Nevertheless, names return which include the first name of the artist herself: hence is everything not in fact a game but rather a series of authentic and instantaneous images, or is it after all nothing other than a staging, a game – how real is life?

The paucity of plot elements, which contradicts all expectation of a cinematic style, as well as the emptiness and loneliness of the persons, enters into a peculiar, sometimes seemingly surreal association with the magic of the sun-drenched expanses of the dreamlike landscape. Just as the fantasy and imagination of the viewer are stimulated, so to the same great extent does the redemption of these visual figures of love founder on a void whose glaze is created, not least of all, by the peculiar blurriness of the photographic representation. The seemingly amateur character of these pictures, which have in no way been treated with any excessive scrupulousness, leaves us with a stimulating incertitude as to their interpretation, one in which the spheres of reality, fiction or dream are scarcely capable any longer of being differentiated. Thus the gaps and the scenic openness of what is presented ultimately set in motion a self-appraisal.

So what remains after “29 Palms, CA”? Perhaps that hope which deviates from the saying of Ruscha that is quoted in the title: “The stronger the photography the better the reality will be!”

translated by George Frederick Takis

The Greater the Emptiness the Grander the Art

von Stefan Gronert

Nicht "Twenty-six gasoline stations", sondern "29Palms, CA"! 42 Jahre nach Ed Ruschas legendärem Buch steht in dem hier vorliegenden keine Tankstelle am Anfang. Stattdessen ist es die offenherzige Radha -orangene Haare, pinkfarbener Overall und einem verschämten, nein verschmitzten, nach unten gesenkten Blick -, mit der dieses Buch beginnt! Und mit ihr und Max - wohlgemerkt: einer Frau -, deren Aussehen demselben Styling entspricht, endet es auch - nachdem sich Radha zwischenzeitlich die Nägel pink lackiert hat, ausgestattet mit derselben Offenherzigkeit und demselben Blick, der nun aber in Verbindung mit ihrer veränderten Miene eine "zickige" Abkehr vom Beschauer offenbart. Ein Beispiel für einen anschaulich nachvollziehbaren Wandel, der in eine große Abbildung einer trostlosen Siedlung unter strahlend blauen Himmel mündet - geradewegs verloren geht eine Figur darin unter.

Bilder, die 1998/99 im grellen kalifornischen Sonnenlicht oder in nicht gerade gemütlichen Räumen spielen. "Spielen" ist das richtige Wort, denn gerade in Anbetracht der Personenbilder bleiben mehr als nur Zweifel daran, ob wir inszenierte Szenen sehen oder nur einfach in die überspannte "Wirklichkeit" einer (Möchte-Gern-) Film-Welt geraten sind. Dabei besitzen nicht alle Bilder denselben Charakter einer grellen Plastikwelt. Beim Blättern durch die Seiten begegnen wir aber auch unscheinbaren, buchstäblich "farblosen" Szenen in nicht definierten Innenräumen oder stillebenartige, unspektakuläre Ansichten im "no- whereland". Was alle Teilnehmer dieser Bild-Welten verbindet, ist die Beobachtung, dass sie erschöpft, verloren, leer oder unsicher über ihr Dasein erscheinen. Fast fühlt man sich an die Leere der Blicke, die Einsamkeit der Menschen in den Großstadtbildern von Manet oder Degas im Zeitalter der frühen Moderne erinnert.

Mit einer Ausnahme weisen alle hier reproduzierten Fotos, die im Original 60 x 70 cm groß sind, in der hier vorliegenden (Größe und) Zusammenstellung aber die Möglichkeiten des Mediums Buch produktiv nutzen, einige Elemente des B-Movies auf: rauchende, nackte, geschminkte und muskulöse Personen, die sich der Vision vom Hollywood-Traum nicht ganz fügen wollen. Schönheit und Verdruss, Erotik und Einsamkeit gehen eine Mischung ein, die den Bruch zwischen Wunsch und Wahrheit offenbaren. Von Ferne fühlt man sich an die in dieser Hinsicht keineswegs so drastischen „Untitled Film Stills“ von Cindy Sherman erinnert. Doch während deren Fotos der siebziger Jahre durch eine kühle, sachliche Darstellungsweise im historisierenden Schwarzweiß charakterisiert sind, zeichnen sich Stefanie Schneiders Fotos durch eine weiche, bisweilen piktoralistisch anmutende Bildsprache mit blasser bis artifiziell-greller Farbigkeit aus.

Wie in vielen anderen Bildern von Stefanie Schneider, die uns oft als Sequenzen begegnen, knüpfen auch diese Fotos gezielt an Wahrnehmungsstereotype des Films an.Im Rückgriff auf die Sofortbildfotografie, von der ausgehend erheblich vergrößerte C-Prints entstehen, erwecken ihre Bilder den Anschein einer Erzählung, ohne dass sie sich aber letztlich in eine linear ablesbare Handlung auflösen. Die Illusion des Narrativen verstärkt jedoch nur die Erfahrung einer Verweigerung derselben. Denn auch die Bildtitel - und auch der Titel dieser Publikation - geben keine wirkliche Hilfe bei der imaginären Konstruktion einer Geschichte. Immerhin kehren Namen wieder, unter denen sich auch der Vorname der Künstlerin befindet: also alles kein Spiel, authentische Momentaufnahmen oder eben gerade eine Inszenierung, ein Spiel - wie wirklich ist das Leben?

Die jeder Erwartung eines Filmstills widersprechende Handlungsarmut sowie die Leere und Einsamkeit der Personen geht mit dem Zauber der sonnendurchfluteten Weite der traumähnlichen Landschaft eine eigenartige, bisweilen surreal anmutende Verbindung ein. So wie Phantasie und Imagination des Betrachters angeregt werden, so sehr scheitert die Einlösung dieser bildlichen Chiffren der Liebe an einer Leere, deren Schmelz nicht zuletzt durch die eigenartige Ver- schwommenheit der fotografischen Darstellung erzeugt wird. Die scheinbare Amateurhaftigkeit der keineswegs penibel bearbeiteten Bilder lässt uns mit einer reizvollen Unsicherheit der Deutung zurück, bei der sich die Sphären von Realität, Fiktion oder Traum kaum mehr differenzieren lassen. So erzeugen letztlich die Leerstellen und die szenische Offenheit des Gezeigten eine Selbst-Besinnung.

Was also bleibt nach den „29 palms, CA“? Vielleicht die Hoffnung, die das in der Überschrift von Ruscha zitierte Diktum abwandelt: The stronger the photography the better the reality will be!

Die jeder Erwartung eines Filmstills widersprechende Handlungsarmut sowie die Leere und Einsamkeit der Personen geht mit dem Zauber der sonnendurchfluteten Weite der traumähnlichen Landschaft eine eigenartige, bisweilen surreal anmutende Verbindung ein. So wie Phantasie und Imagination des Betrachters angeregt werden, so sehr scheitert die Einlösung dieser bildlichen Chiffren der Liebe an einer Leere, deren Schmelz nicht zuletzt durch die eigenartige Ver- schwommenheit der fotografischen Darstellung erzeugt wird. Die scheinbare Amateurhaftigkeit der keineswegs penibel bearbeiteten Bilder lässt uns mit einer reizvollen Unsicherheit der Deutung zurück, bei der sich die Sphären von Realität, Fiktion oder Traum kaum mehr differenzieren lassen. So erzeugen letztlich die Leerstellen und die szenische Offenheit des Gezeigten eine Selbst-Besinnung.

Was also bleibt nach den „29 palms, CA“? Vielleicht die Hoffnung, die das in der Überschrift von Ruscha zitierte Diktum abwandelt: The stronger the photography the better the reality will be!